“The Letter,” 1939, Haddon Heights Post Office

“Everything is sculpture. Any material, any idea without hindrance born into space, I consider sculpture.”

The Artist

Isamu Noguchi, 1904-1988, was a Japanese-American artist who felt most at home in New York City. His neighboring New Jersey legacy is one of sublime beauty, “The Letter,” a WPA era sculpture at the post office in Haddon Heights, near Philadelphia. The elegantly simple figure of a reclining woman writing a letter floats cloud-like above the grounded, wooden post office decor, reflecting her dreamy reverie as she writes what may be a love letter. Mr. Noguchi’s work conveys mystery, sharing his imagination while he challenges ours. The letter writer has a serene smile that suits the friendliness of the town-proud residents by an artist who loved creating work for the public to enjoy. This included sculpture, gardens, fountains, playgrounds, and furniture. His art combined the best of American and Japanese aesthetics.

“News,” 1940, stainless steel bas relief, 50 Rockefeller Center, the former Associated Press Building

As one of the great figures of the twentieth century whose 84 year-long life spanned the globe and whose artistic work included Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, there is so much to learn about Isamu Noguchi. His mother, Leonie Gilmour, from New York City, was a Bryn Mawr graduate who once taught at the Academy of Saint Aloysius in Jersey City. While later working as an editor in New York City, Leonie met the Japanese poet Yone Noguchi. After the relationship ended, Leonie joined her mother in Los Angeles where Isamu was born in 1904. A few years later, following Yone’s invitation, Leonie and Isamu moved to Chigasaki, Japan, where Isamu grew up in a house with a garden by the sea while his mother supported them with teaching. By that time, his father had begun a relationship with another woman. When Isamu was 14, Leonie sent him to the US to attend a progressive school in Rolling Prairie, Indiana, while she remained in Japan with his half-sister. The school founder and a host family in La Porte, Indiana befriended Isamu, and he later graduated from the local high school. Though his childhood was far from traditional and included the disappointment of a distant father, Leonie encouraged his artistic talent and was a devoted mother.

Excelling as a student, Isamu enrolled in pre-med studies at Columbia University. Once introduced to sculpture, he had such a natural ability that he pursued art exclusively. Ironically, his skill was so incredible that it held him back initially, his work criticized for being too perfect. With a Guggenheim Fellowship that funded an apprenticeship with the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi in Paris, Isamu’s work became more personal, which freed him from previous criticism. Interestingly, both sculptors had no mutual language in common except art, but understood each other perfectly, a welcome experience after Isamu’s fraught apprenticeship with Gutzon Borglum, the sculptor of Mount Rushmore. Perhaps reflecting a longing for the father whom he never truly knew, or asserting a new identity, Isamu dropped his mother’s surname “Gilmour” and took “Noguchi” when he became publicly known as an artist. Incredibly, widespread recognition did not occur until Isamu was in his early 40’s. Unfortunately, when traveling to Japan as an artist, Isamu learned that his father did not want him to use the Noguchi surname. On Isamu’s last visit to Japan, while his father was still alive, he did not contact him.

“Childhood,” rough-hewn with a smooth heart, Noguchi Museum

Worldwide travels over six decades as a working artist included friendships with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Mexico and Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning in the US, Greenwich Village neighbors, and collaborations in Japan and Italy. His global works include architecture, perhaps most meaningfully, his design for the Peace Bridges at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, one symbolizing the past and the other, the future. To his disappointment, his design for the main memorial could not be accepted because he was American.

While maintaining a studio in the village of Mure on the island of Shikoku in Japan, where he received inspiration from the Zen gardens, he fell in love with the beautiful actress and singer Yoshiko Yamaguchi (known in the US as “Shirley Yamaguchi”) whom he married in 1951. An anecdote in the museum’s excellent film shares that Isamu wanted the worldly Yoshiko, who worked with Akira Kurosawa and US filmmakers, to wear a kimono at home. She found these uncomfortable, so he designed her a type of pantsuit that had the look of a kimono, but offered more modern comfort. Clothing styles aside, they spent several happy years together in Japan. Sadly, upon their return to the United States for professional reasons, their careers drove them apart.

One account that may best describe the complexity of Isamu’s life was his noble impulse to join fellow Japanese-Americans during their internment in World War II. Living in New York, and not on the West Coast, Isamu, whose name means “courage” in Japanese, was free from this but volunteered to go with the thought of teaching art to boost spirits and develop talent as Brancusi had done for him. The day after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Ginger Rogers, who had commissioned him to create a bust of her, invited Isamu to her home for an initial sitting. He stayed on the grounds for a month as a guest in a studio she had made for him. Isamu finished the movie star’s sculpted portrait in pink marble while living in the Poston, Arizona internment camp on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. During this time he wrote two letters to Ms. Rogers about the work’s progress. As The Washington Post notes, his work may have come to the dancer’s attention through his set designs for the Martha Graham Dance Company where his sister, Alies Gilmour, was a dancer. Despite his good intentions, Isamu found that he had little in common with the farmers, shopkeepers, and laborers in the camp and asked to leave, a process which took several months. One detainee recalled how Isamu would wander out into the desert alone to collect wood to carve. Ginger Rogers treasured her Noguchi portrait, which was a centerpiece in her home until she died, and now is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

“White Sun” 1966, Firestone Library, Princeton University, one of the artist’s favorite sculptures

The Noguchi Museum, New York City

Art at its best is transporting like incredible music, film, or literature that takes us out of ourselves and into the world of the artist’s imagination. As someone who experimented throughout his life by expressing different styles and working with a range of materials (marble, basalt, ceramics, steel, cement, paper, wood, aluminum), Mr. Noguchi risked failure and experienced rejection, but his striving makes the successes soar in a way that defies time and space. Ideal, then, that the complementary works of Spanish sculptor Jorge Palacios, are presently on view along with Mr. Noguchi’s in the latter’s museum in Long Island City, Queens.

Noguchi Museum banners

Jorge Palacios sculpture “Link” at Flatiron Plaza North, sponsored by Noguchi Museum

Second floor museum gallery with view to Akari light sculptures

Second floor museum gallery

At The Noguchi Museum, which the sculptor founded and helped plan, many of the National Medal of Arts recipient’s sculptures relate to time. The Zen Garden, rooted in a serenity that stands outside of time, is beautiful and enjoyed by visitors. One can also admire it from the staircase exit on the second floor as well as from eye level. Flowing water, important to Isamu, creates serenity with the fountain. Central, too, was the artist’s relationship to the material, including an almost spiritual connection to natural elements like wood, clay, and stone, describing carving as a “process of listening,” a quote from his obituary in The New York Times.

There is so much to take in at the museum that it calls for at least a second visit. Everyone will find pieces that stand out. The impermanent works with their interplay with light, water, and nature, appealed to me most on this first visit, perhaps because they are so novel. The beautiful trees are interwoven with Mr. Noguchi’s art.

Zen Garden

View into the garden

Partial garden view from upstairs

The museum’s film about his life features interviews with people who knew Isamu, including a befriended half-brother, and that is also worth a revisit to see in its entirety. A common touching thread in the interviews was that being American and Japanese in the era when Isamu Noguchi grew up, and later, as a citizen of the world, were both often lonely paths for the artist. By living in New York City, however, he returned not to another place, but a home with fellow artists and kindred spirits in the realization of the life he had imagined for himself.

Akari light sculptures

Going up the stairs, where you will find the film, and entering into the world of Akari light was a heavenly surprise. These lamp creations use “electrical light as a sculptural element”. For those interested in reading more about his life, Mr. Noguchi wrote an autobiography Isamu Noguchi: A Sculptor’s World with a foreward by his close friend architect R. Buckminster Fuller. This is available at the museum and on Amazon, which is on order and calls for an Isamu Noguchi 2.0 revisit in “Writing New Jersey Life” and #FridayReads. There is, however, momentum with things, and better to post an introduction before the flurry of the holidays and the Akari and Palacios exhibitions end on January 27th.

“The Kite” stainless steel and reminiscent of “Bolt of Lightning,” 1984, Philadelphia, in honor of Benjamin Franklin. Mr. Noguchi’s plans were on hold for years until a 1979 retrospective of his work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art renewed interest in his art.

Whether visiting as a family, a couple, or on one’s own, and there were one and all, the Long Island City museum is a delight. There is a pleasant café with a select, good menu including coffee and beverages. You can reach the museum by public transportation or car. For those driving, there is street parking, and someone kindly suggested finding parking in a nearby store lot, which you did not read here, but a good faith purchase will put you in good standing. The Socrates Sculpture Park across the street has a free exhibit through March 10th. A blocks up is a new, charming neighborhood place, Flor de Azalea Café, which has some Wifi in a pinch, and thank you to the museum staff for mentioning it.

For travelers, Isamu’s former Japanese studio is now The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum Japan. Other notable public works include the UNESCO Gardens in Paris, the Billy Rose Sculpture Garden in Jerusalem as well as works throughout the United States pictured in the online gallery of The Noguchi Museum in Queens.

The nearby Socrates Sculpture Park

Socrates Sculpture Park views

Backpack book exchange

The Letter

As the museum notes, “The Letter” is a “mural relief” in magnesite, once again displaying Isamu Noguchi’s versatility as a sculptor. The post office has a display case sharing information about what we might call a “3-D mural”. There is a wonderful atmosphere in places that preserve their treasures. Both their appreciation that they are such and their pride in them emanates in a generous spirit. The US Post Office itself released stamps of Isamu Noguchi’s works in 2004, which are still in use.

Under the New Deal, the Public Works of Art Project that brought about “The Letter” and through which it came to my attention, aimed to give work to artists in the Great Depression and existed under the supervision of the US Treasury’s Section of Painting and Sculpture. The intent was for the art to reach as many people as possible, which brought the commissioned artists to the WPA’s newly constructed post offices throughout the country to share their work for the public’s benefit.

“The Letter” in context with a display case (right)

Haddon Heights still charms on a rainy day

Halloween spirit in Haddon Heights

Out and about in friendly Haddon Heights with thanks for the cafe and dining friends’ permission

Town clock, Haddon Heights

Named to honor Algonquin chief and meeting place of New Jersey legislature, historic site, Haddonfield

Cabana Water Ice, Haddon Heights

Halloween spirit, Haddon Heights

Returning to South Jersey, picturesque Haddon Heights where “The Letter” floats timelessly, shares a scenic beauty with Haddonfield and Haddon Township, all the namesakes of Elizabeth Haddon. An English-born Quaker, she sailed to the Colonies alone to begin the settlement of a large area of land in Southern Jersey, southeastern Pennsylvania, and Delaware, bought by her father who had envisioned a peaceful new start for Quakers, unwelcome in England at that time. Too ill to make the journey, his dream was realized by Elizabeth and his name carried on with “Haddon’s Field” where she and her minister husband created a beautiful home and helped to establish the Quaker community. Their courtship, brought to the public’s attention by Lydia Marie Child, a writer and abolitionist who authored the Thanksgiving poem “Over the River and Through the Wood” that became the popular Christmas song, inspired Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to write “Elizabeth,” part of a long poem “Tales of a Wayside Inn”.

Elizabeth Haddon had a shared world view with fellow Quaker Sarah Norris, who renamed her establishment “The Indian King” in gratitude to the “Sachem” in Algonquin, the elder or chief of the Unlachtigo Lenape, the southernmost of the three Lenape tribes in the state. With their knowledge of survival skills, the Lenape, particularly Sachem Ockanickon, were responsible for keeping the Quakers alive through their first winters. Later, when that generosity was not reciprocated, Sarah called her establishment “The Indian King” in gratitude and posted a highly visible sign as a reminder to the settlement of its debt to the Lenape. It was here at the Indian King Tavern that the New Jersey legislature read the Declaration of Independence into the minutes in 1776, and New Jersey became a state on September 20, 1777, with the changing of “colony” to “state” in its Constitution. On this site, the legislature adopted the Great Seal with the cornucopia for the bounty of the Garden State, designed by a Swiss-born artist Pierre Eugene Du Sumitiere.

In the Empire State, the path to find Isamu Noguchi’s works in the New York City he loved started with chats with people uptown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Central Park to midtown to downtown in Manhattan. These began with directions when the iPhone map app slowed with the number of photos, which led to the delightful surprise of fireworks downtown and the Diwali Festival. There was the added warmth of Long Island City, people smiling on the streets, leafy parks, roses and flowers growing skyward through garden gates, and Halloween decorations set up early in happy anticipation. Queens visits were welcome excursions in my Manhattan shoebox apartment days and still are. Being able to dine anywhere in the world in Astoria and shop working my way out from Broadway, especially at the holidays, was a Saturday well spent. Thank you to all the gracious navigators along the way and the staff at the Noguchi Museum.

(Sources: Noguchi Museum, “Central Park: A Template of Beauty”, WashingtonPost.com, pcf.city.hiroshima.jp, Princeton.edu, Rockefellercenter.com, Haddonfield history: @kathleenhelen15, now @kathleenlevey, 2015, theartstory.org, muse.jhu.edu/article/686375/, nytimes.com, summarylevins.com, IndianKingfriends.org, njwomenshistory.org, Avalon.law.yale.edu, A-Z Quotes, Wiki)

“Imagination: Isamu Noguchi” All Rights Reserved © 2018 Kathleen Helen Levey

Sunken Garden at the former Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza, downtown

Fireworks, Festival of Lights, South Street Seaport

Diwali Festival, Southstreet Seaport

Noguchi’s “Landscape of the Clouds,” 666 Fifth Avenue

“Unidentified Object,” 1979, basalt sculpture created in Shikoku, Japan, at the Met and Central Park

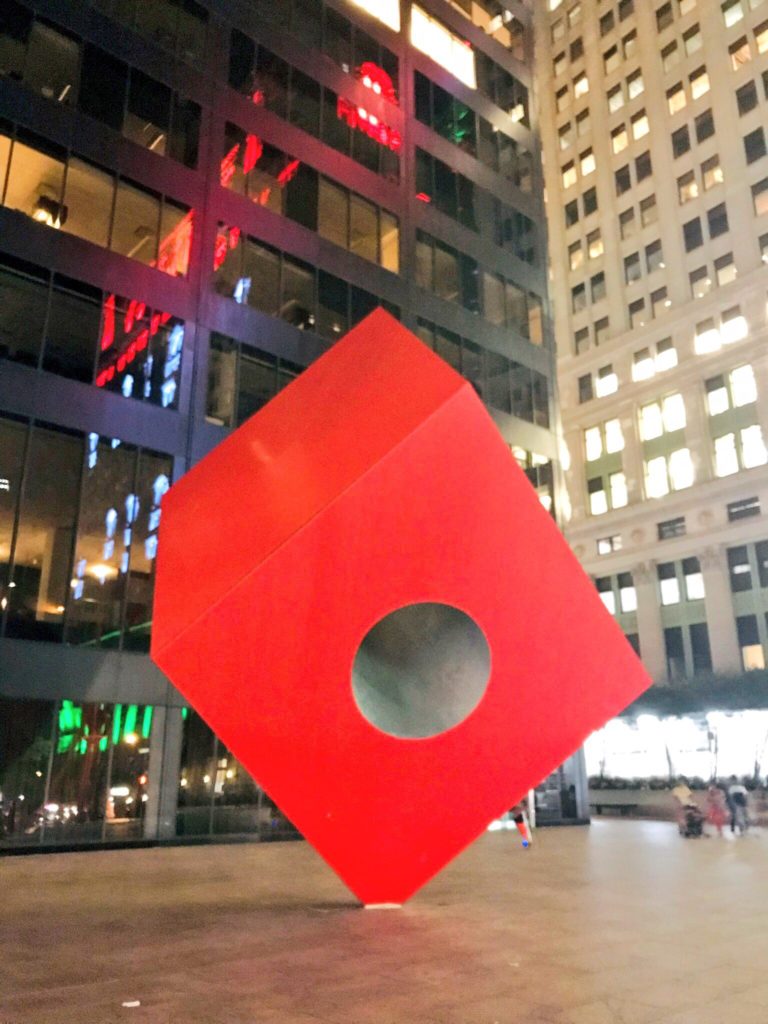

“Red Cube,” 1968, downtown

Jorge Palacios sculpture “Link” with a view of the Empire State Building

Long Island City, Queens

Comments are closed.