Campgaw Mountain, Mahwah, New Jersey

A New Brunswick native and world-renowned poet, Joyce Kilmer, 1886-1918, was married to fellow writer and Rutgers University graduate, Aline Murray, and lived happily and sociably with their five children in leafy Mahwah, the “meeting place” in Algonquin. They knew heartache with the grievous illness of one child, which led to their conversion to Roman Catholicism. A family man, he was exempt from duty in World War I, but enlisted, serving in military intelligence. Loyal, he turned down a commission to stay with his regiment, bravely volunteering to scout ahead on behalf of his men in No Man’s Land where he died from a sniper’s bullet at 31.

…critics sometimes dismiss Joyce Kilmer’s work as being too simple or sentimental, but he was a gifted intellectual, a Columbia University graduate who wrote in structured verse at the end of the Romantic Era. He died before modern poetry had found its voice — and he chose joy, which is not always fashionable. A one-time Latin teacher at Morristown High School and a contributor to The New York Times, both his intelligence and work ethic made him highly employable until his poetry became a success. His poems, many replete with New Jersey references, reflected a love of nature and God. Inspired by looking in his own backyard, the lyric poem “Trees” from Trees and Other Poems (1914) became to American life what the birthday song was to the world, a legacy of celebration:

“Trees”

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.

A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in Summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

Who ultimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

The poem was so popular that it was set to music, first by his mother Annie, a composer, and more popularly, in 1922 by another composer and pianist Oscar Rosbach. Princeton native and distinguished Rutgers University graduate, Paul Robeson, using his wonderful phrasing, recorded a popular version in 1938-9.

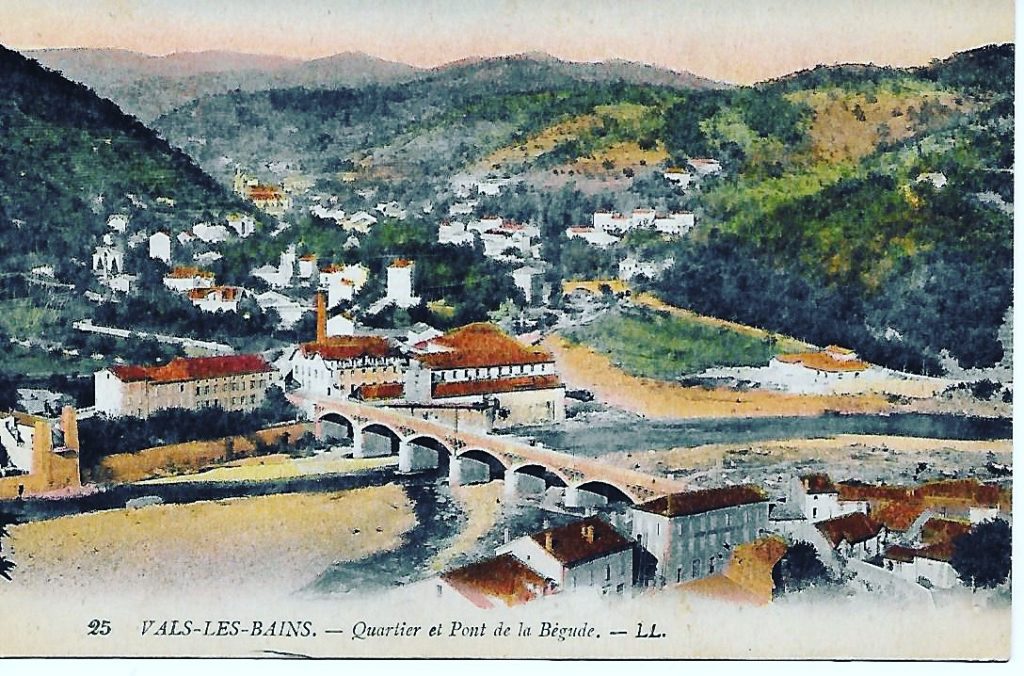

As we observe the 100th anniversary of the United States’ entry into World War I, we remember the sacrifices of those who served like Joyce Kilmer and their families. Some were fortunate like our grandfather, a Newark native who was stationed stateside, others returned from overseas irretrievably changed emotionally and physically from trench warfare. The WWI postcard is from our great-uncle who like Joyce Kilmer was stationed on the Western Front. Our uncle, a beloved brother and son, wrote to his family with great affection on these lifeline postcards. He suffered from “gas and shell shock” meaning that he inhaled the poisonous gas thrown by enemy forces into the trenches and also suffered the “shock,” what we call PTSD “post traumatic stress disorder” today. Unlike Joyce Kilmer, our uncle came back home. He was still a gentle, kind man, but returned to a redefined life, fortunate in that he had family who loved him.

Incredibly, Joyce Kilmer still wrote poetry on the battlefront. Though most was in draft form, ‘A Blue Valentine,” dedicated to his wife Aline, blends faith and romance with the speaker addressing “Right Reverend Bishop Valentinus”:

…It seems appropriate for me to state

According to a venerable and agreeable custom,

That I love a beautiful lady.

Her eyes, Monsignore,

Are so blue that they put lovely little blue reflections

On everything she looks at…

It is like the light coming through blue stained glass,

Yet not quite like it,

For the blueness is not transparent,

Only translucent.

Her soul’s light shines through,

But her soul cannot be seen.

Joyce Kilmer’s legacy was not only his family and his works, but namesake New Jersey schools, the Joyce Kilmer House and a park, both in his New Brunswick hometown, a Bronx park at the Grand Concourse, and a memorial forest in North Carolina. Worldwide celebrations for Arbor Day, the last Friday in April in the United States, often include the reading or singing of his poem.

As for the critics of Joyce Kilmer’s work, one might say never out of step, just sometimes out of fashion.

Our uncle’s postcard from Vals-Les-Bains, France, a spa town before World War I

Quotes from the works of Joyce Kilmer. Published in ‘Writing New Jersey Life” blog at kathleenhelenlevey.com, June 21, 2017 Adapted text from “The Moral Quandary of Heels” All Rights Reserved © 2013 Kathleen Helen Levey

The New Jersey Pinelands were the source of Dr. James Still’s inspiration, where his ingenuity led him to flourish as a homeopathic physician. Known in South Jersey and the Philadelphia area as the “Black Doctor of the Pinelands,” Dr. Still, 1812-1882, became an admired healer and one of the wealthiest men in South Jersey at a time when a formal medical education was not available to him.

The New Jersey Pinelands were the source of Dr. James Still’s inspiration, where his ingenuity led him to flourish as a homeopathic physician. Known in South Jersey and the Philadelphia area as the “Black Doctor of the Pinelands,” Dr. Still, 1812-1882, became an admired healer and one of the wealthiest men in South Jersey at a time when a formal medical education was not available to him.  Conscious of being a role model, at times in his autobiography, Dr. Still directly addresses readers: “Rise in the morning with a cheerful spirit, and try to retain it during the day” and “Merit alone will promote you to respect.” More specifically, he encouraged, “…I would like to be an example to my sons, and all other poor young men who shall be so unfortunate as I was to have to commence the battle of life without education or pecuniary means.” Dr. Still’s son James, Jr., became the second African-American man to graduate from Harvard Medical School, doing so with honors.

Conscious of being a role model, at times in his autobiography, Dr. Still directly addresses readers: “Rise in the morning with a cheerful spirit, and try to retain it during the day” and “Merit alone will promote you to respect.” More specifically, he encouraged, “…I would like to be an example to my sons, and all other poor young men who shall be so unfortunate as I was to have to commence the battle of life without education or pecuniary means.” Dr. Still’s son James, Jr., became the second African-American man to graduate from Harvard Medical School, doing so with honors. Quotes from Dr. Still’s “Early Recollections and Life of Dr. James Still”. Adapted text from “The Moral Quandary of Heels. All Rights Reserved © 2013 Kathleen Helen Levey. Published on “Writing New Jersey Life” on 6/21/17

Quotes from Dr. Still’s “Early Recollections and Life of Dr. James Still”. Adapted text from “The Moral Quandary of Heels. All Rights Reserved © 2013 Kathleen Helen Levey. Published on “Writing New Jersey Life” on 6/21/17