“What you do will show who you are.” Thomas Alva Edison

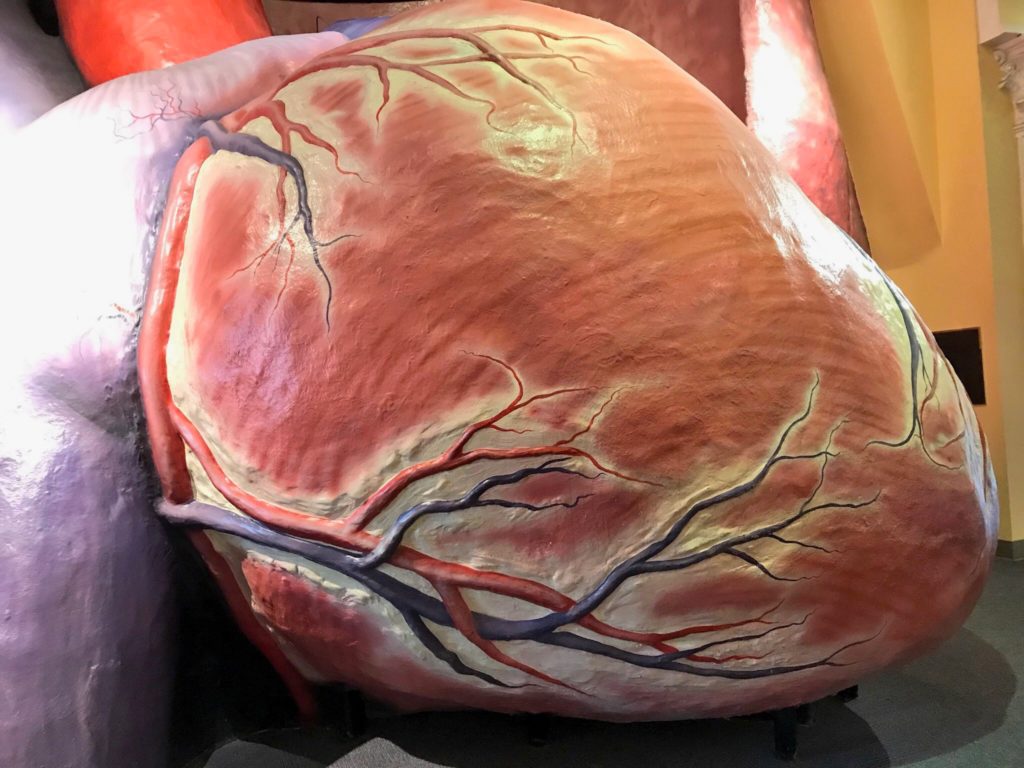

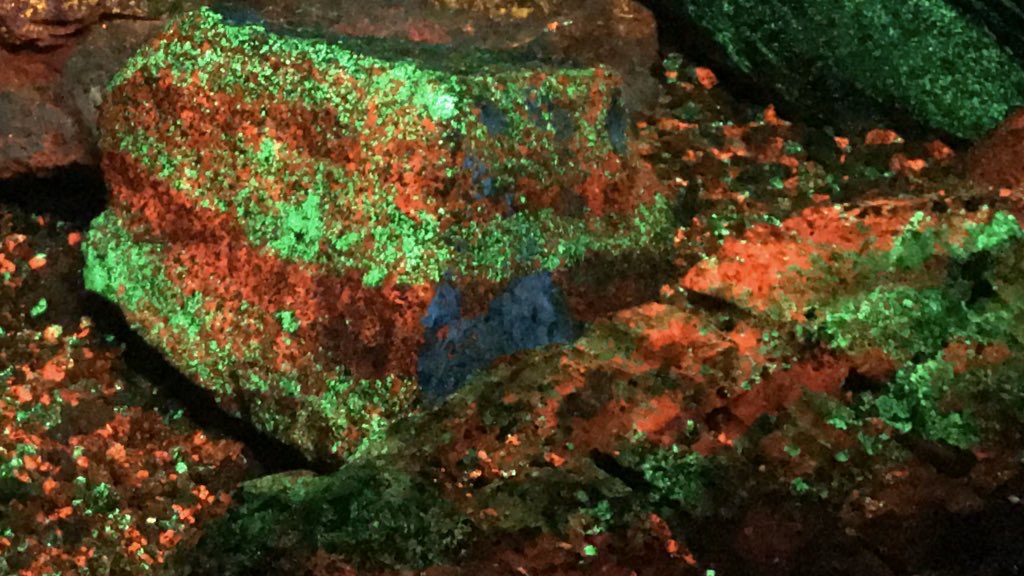

From the rainbow beneath the Earth to the stars in the sky, Sterling Hill Mining Museum encompasses every aspect of science. Described as a “gem” by Fodor Travel Guide, the nonprofit museum combines geology, history, and magic in a place that fascinates visitors of all ages as they experience one of the best tours in the state – or anywhere. On the National Register of Historic Places, the museum’s fluorescent minerals are on display in both the Smithsonian Institution and the Museum of Natural History. The incredible Rainbow Tunnel, part of what is the largest collection of fluorescent minerals in the world, and the mining museum are about an hour’s drive from New York City and slightly longer from Scranton, as is the neighboring Franklin Mineral Museum.

The Mining Museum

Dedicated to learning for all ages and the inspiration of future scientists and engineers, Sterling Hill Mining Museum is continuously evolving as its new website shows. Return tours like the one I enjoyed in the late summer bring more discoveries. In operation for more than 300 years, Sterling Hill Mining Museum is the fourth oldest mine in the country. Passing through picturesque Ogdensburg and going up the museum’s long driveway, visitors experience the awe-inspiring sight of the sky-high conveyor of the former working mine. A visit begins with a warm welcome when buying tickets for the two-hour museum and mine tour and/or Discovery Digs (fossil and mineral), sluice mining, the GeoSTEM Academy, or periodic special tours. Observations that staff share on the tours and in museum YouTube videos are, “If you can’t grow it, you have to mine it…” and “almost everything man-made depends on mining for its production,” capture the breadth of what the museum has to offer.

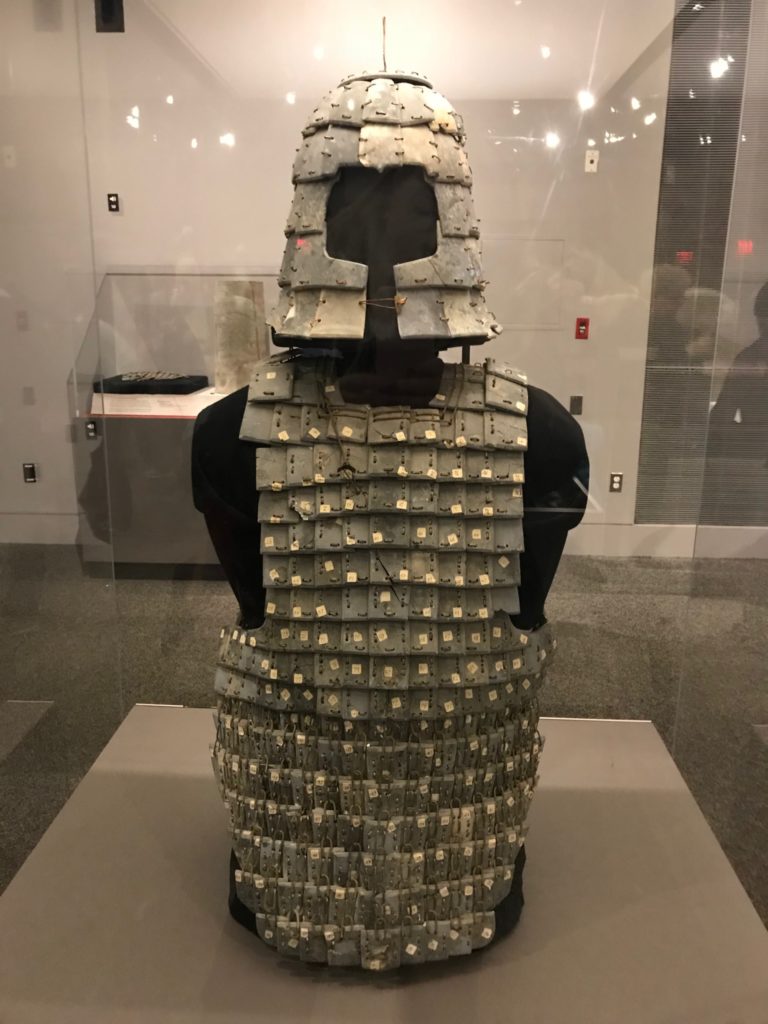

Touring the mine means walking through a 1/4 mile of white marble tunnels where the temperature is about 56 F (13 C) year-round. Of the 35 miles of tunnel, only the ground level remains open to the public. The mine floors are not perfectly smooth, but the tour is stroller and wheelchair accessible. Wearing layers and water-resistant clothing and shoes is helpful as is bringing protective eyewear for digs. The mine tour includes a simulated blast among the representative sights.

The tour begins in Zobel Hall Museum, which was the miner’s change house during the era of the New Jersey Zinc Mining Company, 1852-1986. Striking among many treasures in the room are the giant dinosaur skull, the incredible periodic table, and miners’ helmets in the glass cases. The fluorescent minerals in the curtained corner room give a preview of the remarkable display to come. Behind the miners’ helmets is the Oreck Mineral Gallery with beautiful minerals from around the world showcased with state-of-the-art lighting.

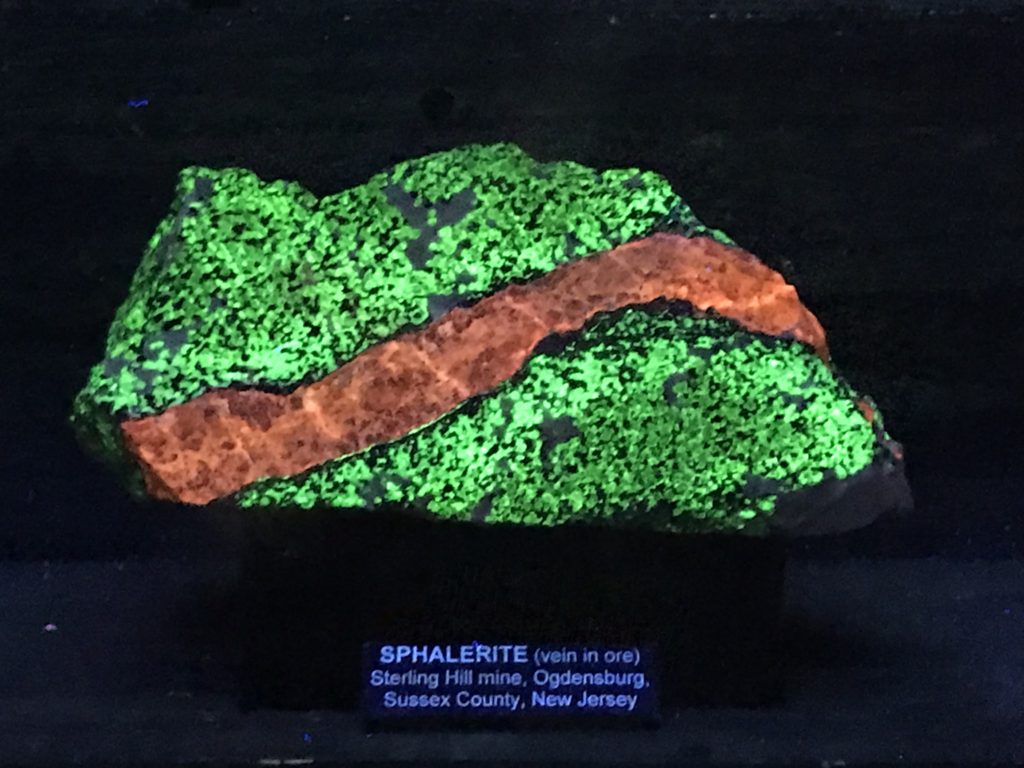

The tour also includes the original mine and the Warren Museum of Fluorescence with a collection of more than 700 specimens of glow-in-the-dark minerals. (Interestingly, different kinds of ultraviolet light, longwave and shortwave, bring out different colors.) Wonderful in itself, the Warren Museum sets the stage for the remarkable Rainbow Tunnel. Of the 356 minerals found in Sterling Hill Mine, the discovery of as many as 80 fluorescent ones in the early 90s brought Sterling Hill Mining Museum worldwide renown.

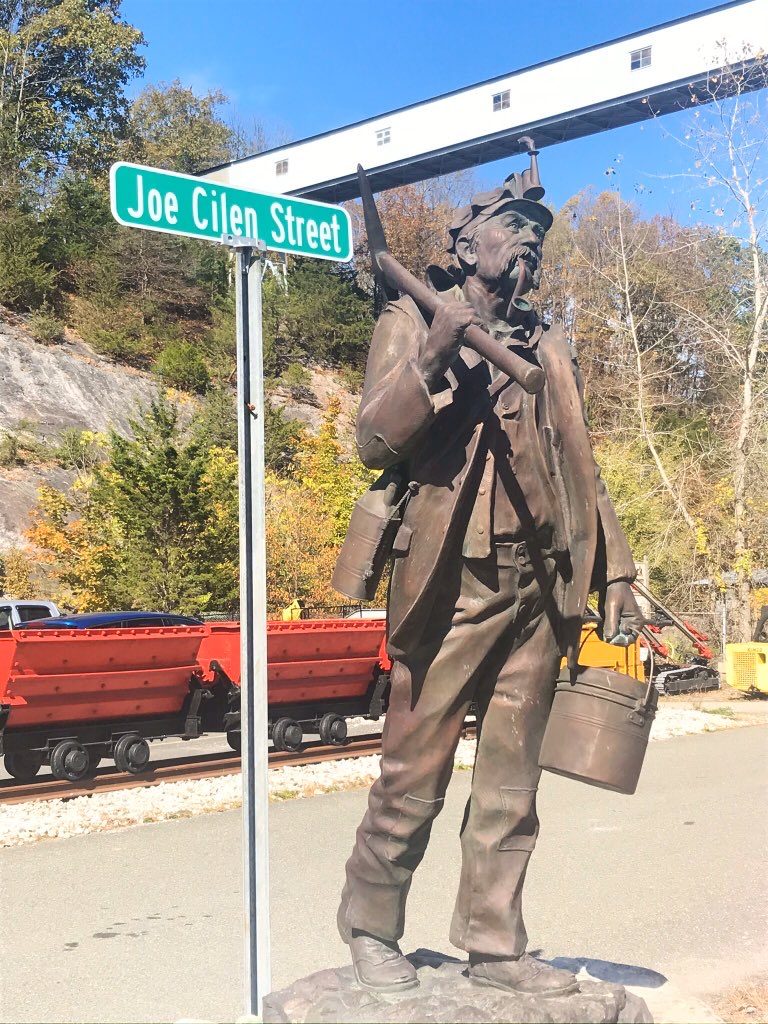

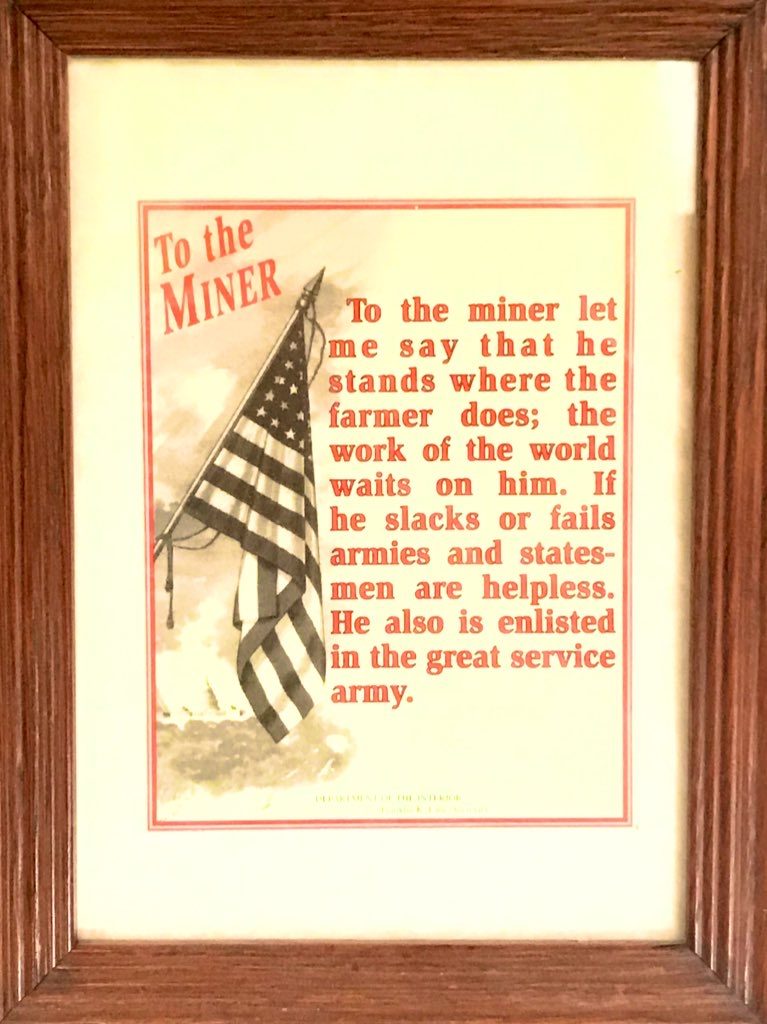

Mining Life

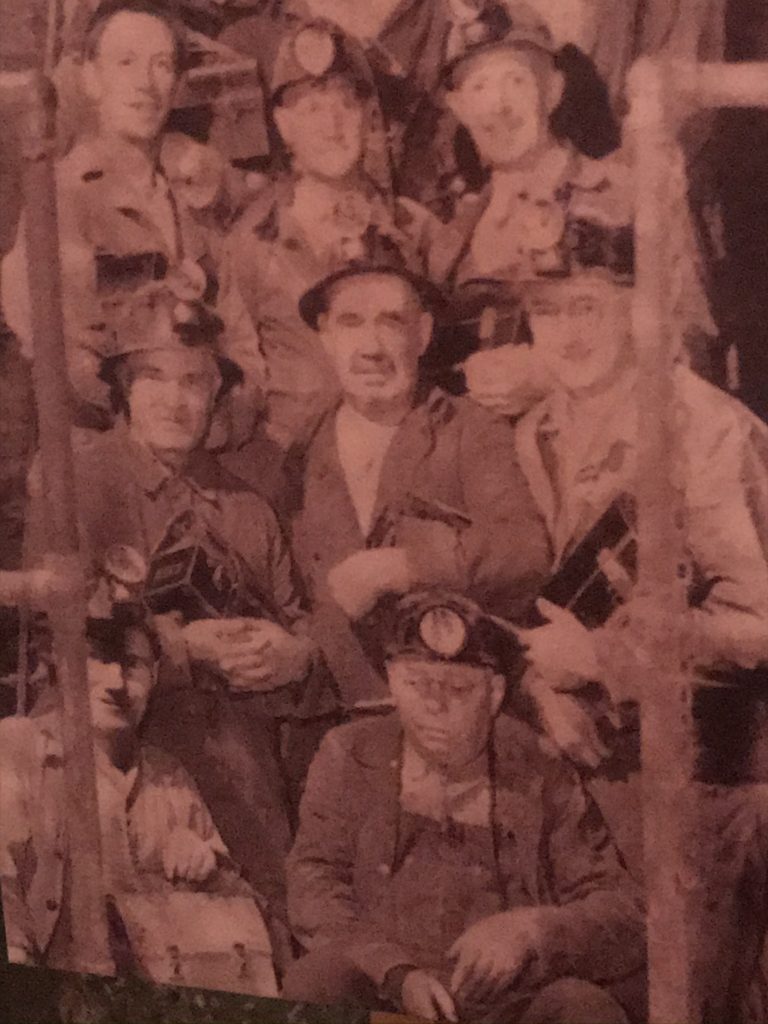

In Zobel Hall at the start of the tour, miners’ lockers remain with photos of those who contributed to the development of the museum. Miners’ work clothes hang from the ceiling as they did nightly to dry out for the next day. Jobs at the mine included: drill runners or lead drillers, muckers “who moved the blasted ore,” cage men who transported men and supplies on the “man cages” or elevators which descended at 900 feet per minute, and the shift bosses. Recovered footage of daily life at the mine in the 1930s is available in Sterling Hill Mining Museum videos on YouTube with links on the museum’s homepage. Extracting zinc, used to make pennies, paints, shoes, boots, ceramics, vitamins, sunblock, tires, and brass among other things, made a profit until the 1980’s when the costs of running the mine exceeded those.

White lung disease was the hazard of working in the zinc mines as black lung was of the coal. The miners of the late 1800’s came from Poland, Russia, Hungary, and other Slavic countries, some directly from Ellis Island. The new website shares the diaries of miner John Kolic, who worked in the mine from 1972 until the mine closed in 1986, and contributed to the museum from 1989 until 2014. To follow newly released diary chapters, events, and topics ranging from chemistry to geology to ghosts, sign up for the Sterling Hill Mining Museum Newsletter. Having family on our father’s side who worked in the coal mines in Northeastern Pennsylvania, visiting the mine and following its history is also of personal interest.

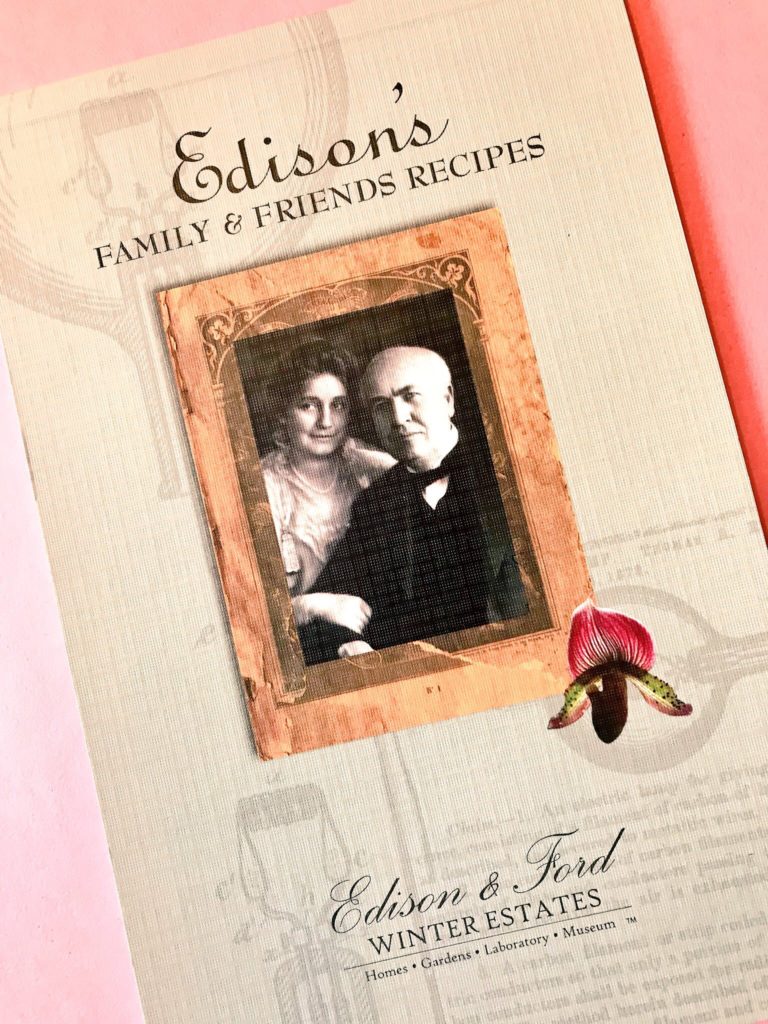

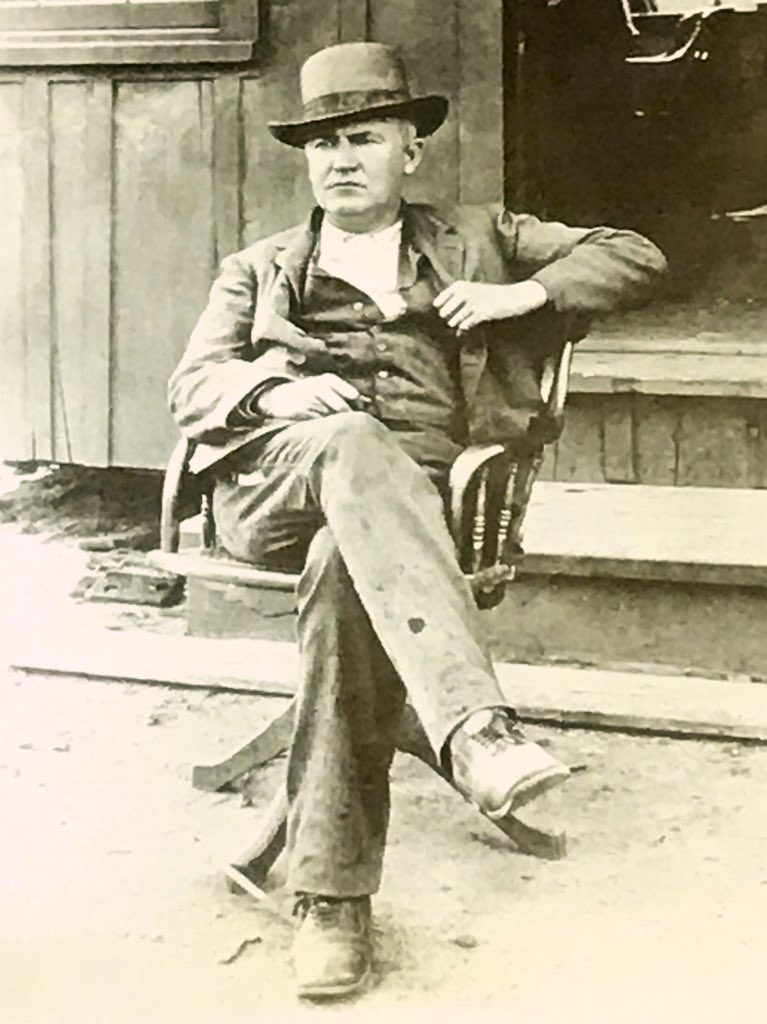

Thomas Edison, with ties to Ogdensburg, had a mining business, the Edison Ore-Milling Company, that traversed between there and Sparta following the company’s origin in Bechtelsville, Pennsylvania. Mr. Edison invented what came to be known as the Edison Cap Lamp for the Mine Safety Alliance Company (MSA) in 1914. Battery operated, the cap allowed miners to see for as long as 12 hours without the danger of using flammable gas. Thomas is honored by the Edison Tunnel at the museum. This weekend, the film “The Current War” about the competition between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse & Nikola Tesla will be released. In addition to the Sterling Hill Mining Museum and Thomas Edison National Park in West Orange, science and history buffs can also visit the charming Queens home of another light bulb inventor Louis Howard Latimer, post in progress with a link to come, part of the Historic Houses of New York

From Mine to Museum

Brothers Richard and Robert Hauck bought the closed mine in 1989 with the generous thought of sharing it with the public as a museum. The moving addition of the steel remnant from the World Trade Center is a donation from an area company that assisted after 9/11, also giving visitors an idea of the character of those behind the museum.

Ongoing projects include a railroad caboose restoration. The museum offers a snack bar (with rock candy 😉) and a gift shop both of which help support this educational nonprofit. Donations of minerals, fossils, and mining artifacts are welcome as are memberships and gifts of support. The museum is a sponsor of a STEM Scholarship Award for college students.

The popular museum has about 40,000 visitors a year. Groups are welcome for tours scheduled two weeks in advance. Please call (973) 209-7212. The ticket prices for the two-hour tour are incredibly reasonable for this area: adults, $13, senior adults $12, children (4-12) $10 ($9 on a group tour), and free for under 4. Tours are daily at 1 p.m. till the end of November, weekends at 1 December through March, daily at 1 April through June, and daily at 10 a.m. and 1 p.m. July through August. Sterling Hill Mining Museum welcomes anyone with interest in science or engineering who would like to be a guide. The next GoSTEM Academy is Saturday, November 2nd for those who would like to register.

Posted with thanks to @sterlinghillminingmuseum for following on Instagram. In addition to the museum’s Instagram and Facebook pages, you may enjoy their informative YouTube videos.

The Ellis Astronomical Observatory

A new discovery on a brief follow up trip this month was the intriguing Ellis Astronomical Observatory. Far from city lights, the Ellis Astronomical Observatory offers clear views of the night sky with reflector telescopes and safe views of the sun through a Hydrogen-Alpha one.

The next viewing is for the transit of Mercury on the morning of November 11th, which is the sighting of the silhouette of Mercury against the sun. In each century, there are 13 transits of Mercury. The next one will be November 3, 2032. To make a reservation for this November, contact Bill Kroth (973) 209- 7212 or Gordon Powers: (973) 209-0710.

The Mine’s Namesake

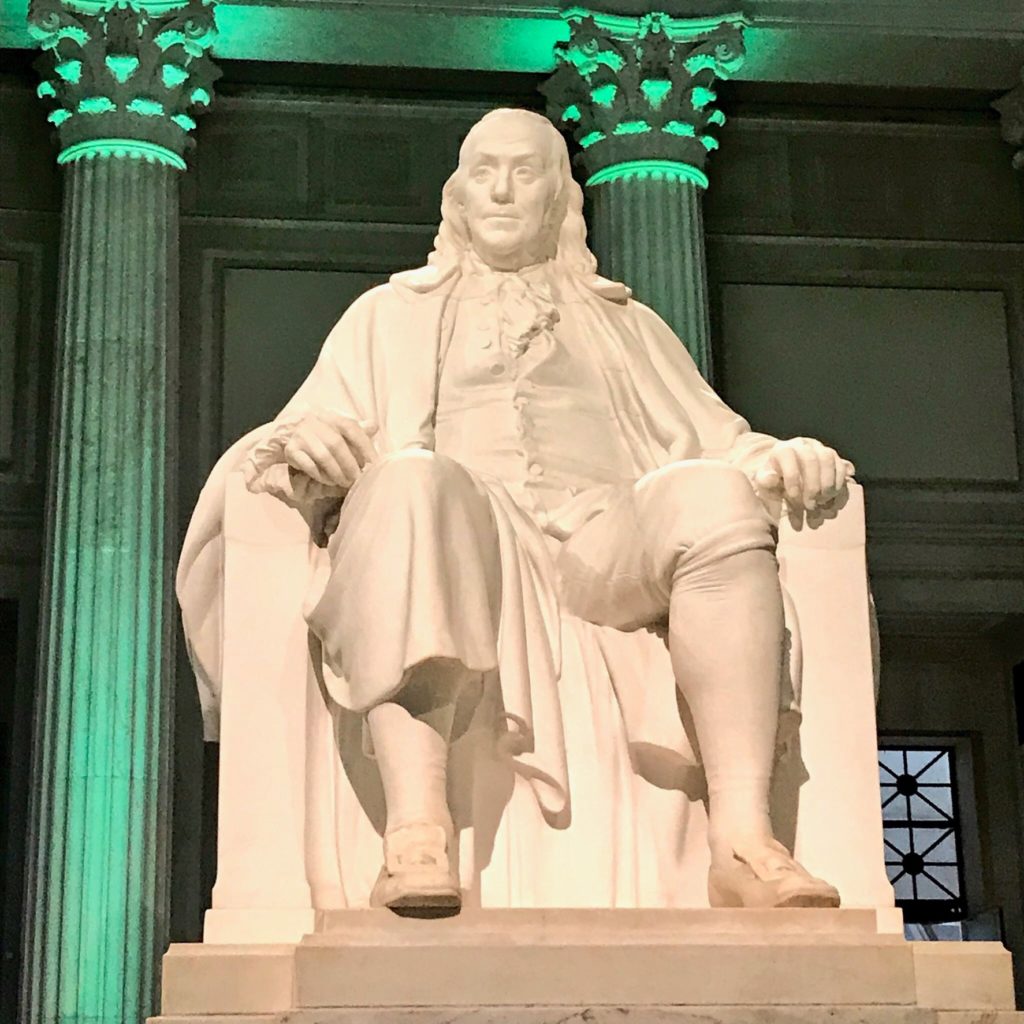

Following the initial Dutch entrepreneurs who sought copper, Lord Stirling, 1726-1783, often spelled as “Sterling” in records of the 1700’s, was one of the early owners of the mine. Serving in the Continental Army from 1775 until his death in 1783, he first led the Battalion of East Jersey and then the 1st Maryland Regiment to win the Battles of Trenton, Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth. Like many of his wealthy compatriots in the war, William used his own money to provide supplies and weapons for his men.

Considered flamboyant by some for his pursuit of a Scottish title, New Yorker William Alexander, Lord Stirling walked away from it without hesitation to serve his country in the fight for independence. With respect, General Washington called his brigadier general “Lord Stirling” as did William’s officer peers throughout the Revolutionary War. The issue of the title may have reflected the historical Scottish-English and English-Colonial tensions of the era. A Scottish high court granted William the title, which the English House of Lords later rescinded. The title would have given William ownership of a great deal of coastal land in New England and Nova Scotia.

Loyal, William helped stop the Conway Cabal, the 1777 conspiracy by General Conway and some Continental officers to remove George Washington for being a “weak general”. Appalled by such “wicked duplicity of conduct” (ushistory.org), William informed General Washington of the plot and supported him as he had done his previous commander General William Shirley, also an early governor of Massachusetts, in the French and Indian War. William’s courage at the Battle of Long Island earned him a newspaper headline, if not an official title, and the praise of General Washington as “the bravest man in America”. General Washington left William in charge of the Continental Army in the general’s brief absence and before the war had given William’s daughter Catherine away at her wedding. Catherine’s mother and William’s wife was Sarah Livingston, sister of William Livingston from Union’s Liberty Hall, who was a signer of the US Constitution and the first governor of New Jersey. Sarah accompanied William to Valley Forge and, a capable accountant, acted as William’s agent in managing properties.

Accomplished in mathematics and astronomy, William founded King’s College, precursor to Columbia University, of which his grandson William Alexander Durer was later president. William died shortly before the official end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, which is why he is not well-known today. In some ways, William’s attitudes were reflective of his peers, in other ways, not. Historically, Lord Stirling may best be remembered as a brave man of the American Revolution. The Lord Stirling Festival returned to Basking Ridge earlier this month at Lord Stirling Park Environmental Education Center to honor William for his contributions. William’s gravesite is in Trinity Churchyard in New York City, along with his wartime compatriot Alexander Hamilton. Today, William’s love of mathematics and astronomy echo in the scientific pursuits at the museum.

Franklin Mineral Museum

Franklin Mineral Museum is another geological treasure trove near Sterling Hill Mining Museum, both in the Franklin District. Also known for its florescent minerals, the Florescent Room at the museum celebrates this geological bounty of the region as it does the miners.

Displays in the museum begun by a local Kiwanis Club also include types of zinc that was the basis of the Franklin District’s mining from the mid-1800s, as Sterling Hill also notes: Franklinite, discovered in the Franklin District mines, zincite, rare except in the Franklin and Sterling Hill area, and willemite. The museum literature explains that the discovery of fluorescent minerals came about when sparks from early electric equipment in the mines made the rocks glow.

For visitors with children who like digging, dinosaurs, and tunnels, this is a wonderful complement to Sterling Hill. Another warm welcome from staff who enjoy sharing all that the museum has to offer is in store, though kindly ask permission regarding taking photos inside the museum.

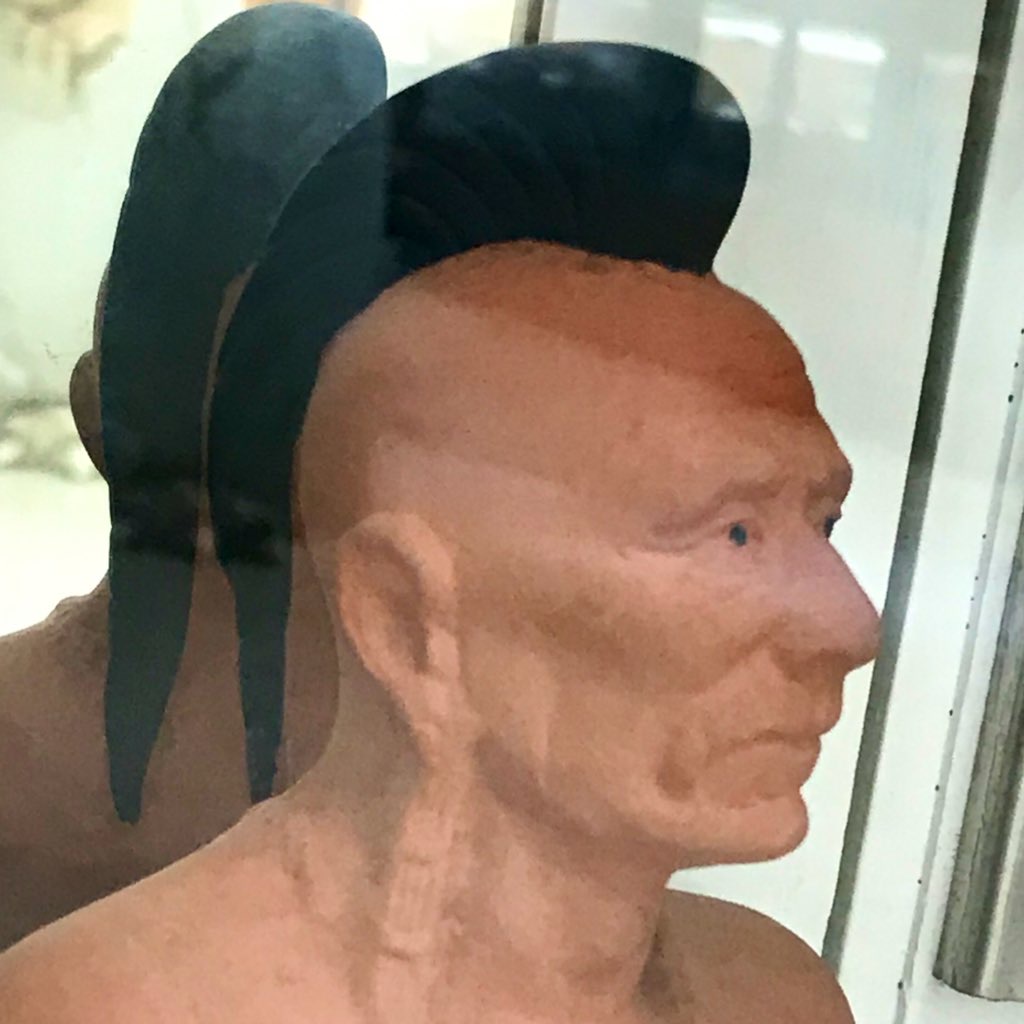

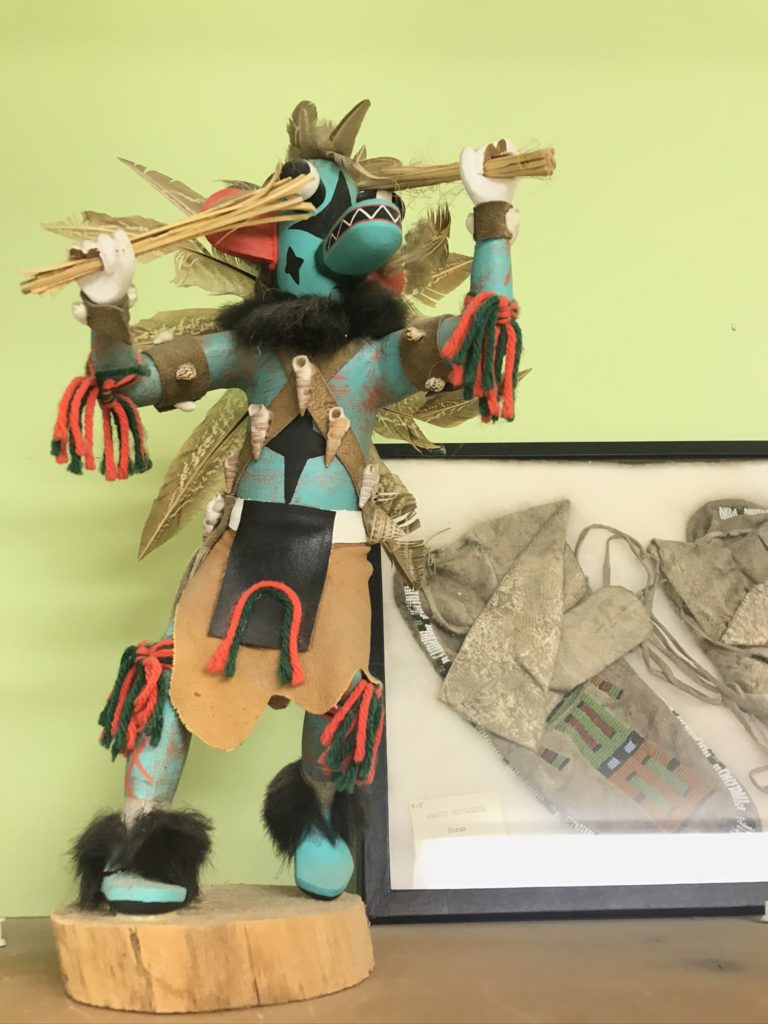

A fascinating surprise was Welsh Hall, named after Wilfred “Bill” Welsh, a teacher who had served with the Navajo Code Talkers during World War II. Mr. Welsh donated his collection of Native American artifacts and fossils to the museum as well as his worldwide collection of minerals, acquired with his wife Mary.

Sussex County has beautiful family farms offering fall events and Christmas tree farms and skiing as the weather changes. For warm weather fans, the Sussex County Miners baseball team plays in Augusta. Off-season at their Skylands Stadium home there is a Christmas Light Show & Village, which takes visitors from fluorescent to holiday bright.

(Sources: sterlinghillminingmuseum.org, franklinmineralmuseum.com, youtube.com, americanhistory.si.edu, ethw.org, falconerelectronics.com, Ogdensburg Journal, nytimes.com, abc7ny.com, northjersey.com, mountveron.org, sterlinghistoricalsociety.org, lordstirling.org, ushistory.org, battlefields.org, brownstoner.com, tripadvisor.com, njherald.com, smithsonianmag.com, Franklin Mineral Museum pamphlets, tworivertimes.com, nyu.edu, William Alexander by Paul David Nelson, Past and Present: Lives of New Jersey Women, tapinto.net, americanrevolution.com, iment.com/maida/familytree/henry/bios/lordstirling.htm, Wiki)

“From the Earth to the Stars: Sterling Hill Mining Museum” All Rights Reserved © 2019 Kathleen Helen Levey